For a lot of middle and high school horn players, reading bass clef is confusing enough. But the horn has one other little detail to think about whenever you see any bass clef writing – old notation vs. new notation?

Old Notation

Composers from the Classical, Romantic, and even later eras often used what is known as old notation. This kind of bass clef writing involves writing the notes one octave lower on the bass clef than they will be played. Nothing else changes – if the part is for horn in E then you still must transpose the notes as usual. Another way to think about it is old notation is played an octave higher than written.

As far as I am aware, the actual origins of this system of bass clef writing are not totally clear. It likely came about through necessity – many times the two horn parts were written on one stave, so when the 2nd horn was playing low it was ‘easier’ to notate those notes one octave too low in the bass clef (so they still “look” low, and the eye can follow it easier) and this also gave the composer a lot of room above the 2nd horn notes to write the 1st horn part on the same stave.

Here’s a small excerpt from Beethoven’s 7th symphony 1st movement, demonstrating a bit of what I mean:

You can see in the last two bars of the horn (Cor.) line, that although the two horns are one octave apart, there is still quite a lot of room above the 2nd horn note. Beethoven could have even written the 1st horn part two octaves higher, and he would only be slightly above the staff! Keeping notes in the staff made things much easier when everything was hand-written – likely the copyist simply wrote exactly what he read, and over time, this became tradition.

Keep in mind that this started well before Beethoven, but this excerpt is a good example of the benefits of such a system. Although it started relatively early on, be mindful that many later composers – such as Shostakovitch, Wagner, and Strauss – used old notation.

New Notation

New notation is simply bass clef writing that is written in the correct octave. Most new music today is written in this notation system, since programs like Finale and Sibelius have made writing scores and parts much simpler, and there is no longer a need to combine as many instruments as possible on the same stave.

If you have any experience reading piano music (or any other instrument that plays in both treble and bass clef) then you already know how this notation works.

Old vs. New Comparison

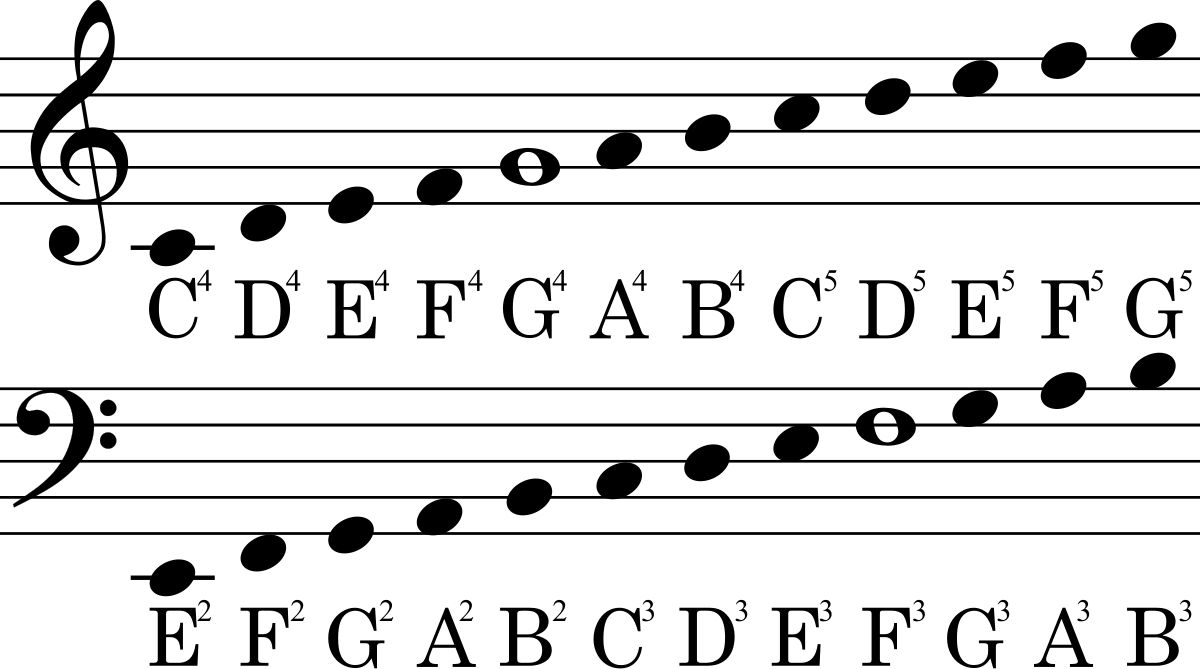

If you’re still a bit confused, the following C major scale should give you a better visualization. Each measure notates the exact same pitches!

How to Tell Old vs. New

Generally speaking, the best way to tell old notation vs. new notation is simply common sense.

My “checklist” if I don’t know whether a piece is old or new notation is this:

- If the piece was in new notation, would the bass clef notes be unreasonable low (lower than the F at the bottom of the bass clef). It’s likely old notation.

- If the piece was in old notation, would the notes be too high to make sense in bass clef (notes continuously written above second-space C). It’s likely new notation.

- Looking at the score, would the part have any unusual voice crossing in either old or new notation (lower than a tuba or other bass voice, higher than a trumpet or other soprano voice, etc.). It’s usually whichever makes the most sense in terms of registers

- If the piece is written after 1920, it’s often (but not always) new notation.