While jazz horn wasn’t what I had planned to write about this week, I read a wonderful blog post about Julius Watkins over at HornMatters.com, and thought that it was worth sharing.

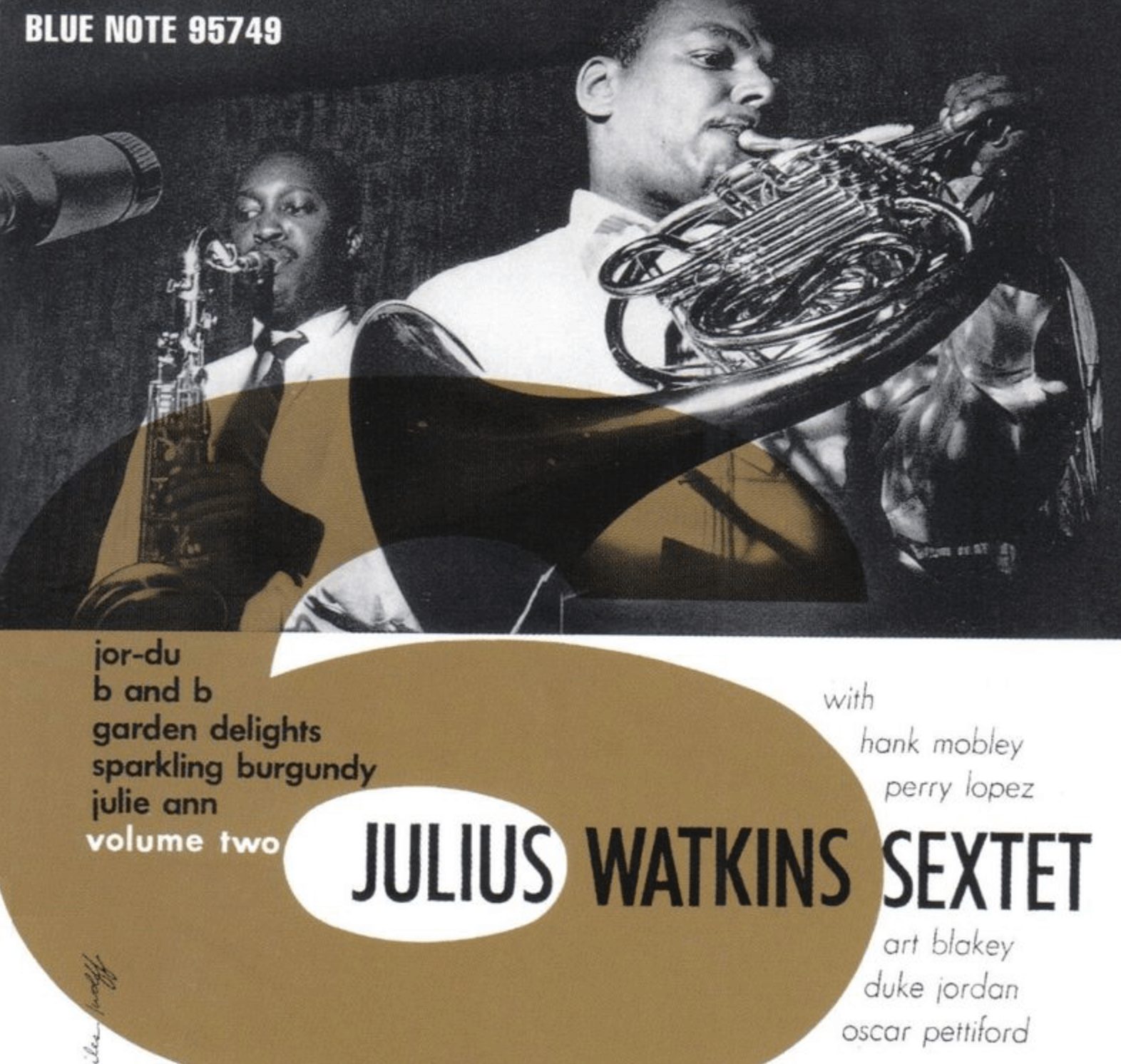

Julius Watkins

The main topic of the blog post was Julius Watkins ( 1921-1977) who basically paved the way for the French horn in jazz music.

I have heard of Julius Watkins before, but it wasn’t until John’s blog post that I actually heard him play, and the couple of videos that he posted are impressive.

A dissertation by Patrick Smith mentions his immense technique:

Numerous personalities, including music critics Leonard Feather and John Wilson, remarked at his pure tone and authoritative command of the instrument’s range, while other professional horn players were taking note of Julius’ accomplishments. “There were other French horn players in town who were doing a lot of record dates and various other things,” said Warren Smith. “One of them was named Ray Allonge. He was working for the musician’s union. Ray told me that Julius could easily play an octave above what Ray could play. This really was saying something in a number of ways because Ray was the first call Caucasian French horn player who got all of the gigs. But even the French horn players in that elevated level of money-making – that’s why I’m making that designation – knew that Julius had these capabilities.

A video of him soloing with Quincy Jones and his band, recorded in 1960, covers an enormous range. Take a listen:

It starts off on a high C, and that’s not even the highest note that he plays.

It’s also worth noting how even and easy everything looks – whether he’s above the staff or below it. In fact, if you mute the video and watch it back it’s difficult tell what register he’s in.

How he chose to play jazz on the French horn is both a practical story and a somber reminder of the history of racism in both Classical music and in the United States.

From Patrick Smith’s dissertation again:

As a sixteen-year old African-American horn player in the 1930s, his chances of earning a position in a symphony orchestra were effectively nil…By the summer of 1937, Julius had determined that his musical career path would be different from that of any other performer of his instrument up until that time. “I wanted to be a soloist,” said Watkins in an interview with Downbeat Magazine. “There is very little repertoire in Classical music for solo horn. So, I learned to jazz.”

Not only was his range impressive, but his technique was incredibly fluid. Listen to him play some long, lyrical solo lines and then fast technical passages with the saxes:

Legacy

While my own knowledge of Julies Watkins is lacking, I hope this (and the Horn Matters article) inspire you to do some further digging on the man behind horn in jazz.

While his recordings may not be the easiest to find (a complete listing of them is on his Wikipedia page), if you’re at all interested in jazz his musicianship and technique are worth study.

(One other thing from the Horn Matters post – a horn player named Vincent Chancey studied with Julius Watkins and one of the topics Julius covered was different fingerings for playing with different instruments and different registers for solo lines depending on the projection/volume needed. Very interesting!)

In addition to Vincent Chancey, there are countless other horn players that have followed in the footsteps of Julius Watkins: John Clark, Tom Varner, Vincent Chancey, Mark Tayler and many others.

If you love the French horn and jazz, don’t let “tradition” or a close-minded director’s idea of “what a jazz band is” stop you!

PS: If you’re looking to learn how to improvise, the Chop-Monster series is a great way to start. (That may or may not be one of my quarantine projects)!

Leave a Reply